Researchers from the Institut Pasteur and Inserm have found that when mother mice consume dietary emulsifiers, it can negatively affect the gut microbiota of their offspring. These early changes in gut bacteria are linked to a higher risk of chronic inflammatory bowel conditions and obesity later in life. The findings point to possible health effects that extend across generations and underscore the need for human studies, particularly to understand how early-life exposure to emulsifiers may influence long-term health. The study was published in Nature Communications.

Emulsifiers are additives widely used in processed foods to improve texture and extend shelf life. They are common in products such as dairy items, baked goods, ice cream, and some powdered baby formulas. Despite their widespread use, scientists still know relatively little about how these substances affect human health, especially their impact on the gut microbiota.

How the Study Was Conducted

The research was led by Benoit Chassaing, Inserm Research Director and Head of the Microbiome-Host Interactions laboratory (an Inserm unit at the Institut Pasteur). In the study, female mice were given two commonly used emulsifiers, carboxymethyl cellulose (E466) and polysorbate 80 (E433), starting ten weeks before pregnancy and continuing through pregnancy and breastfeeding. The researchers then examined the gut microbiota of the offspring, which had never directly consumed these emulsifiers themselves.

The results showed that the young mice experienced noticeable changes in their gut bacteria within the first weeks of life. This period is especially important because mothers naturally pass part of their microbiota to their offspring through close contact.

Disrupted Gut-Immune Communication

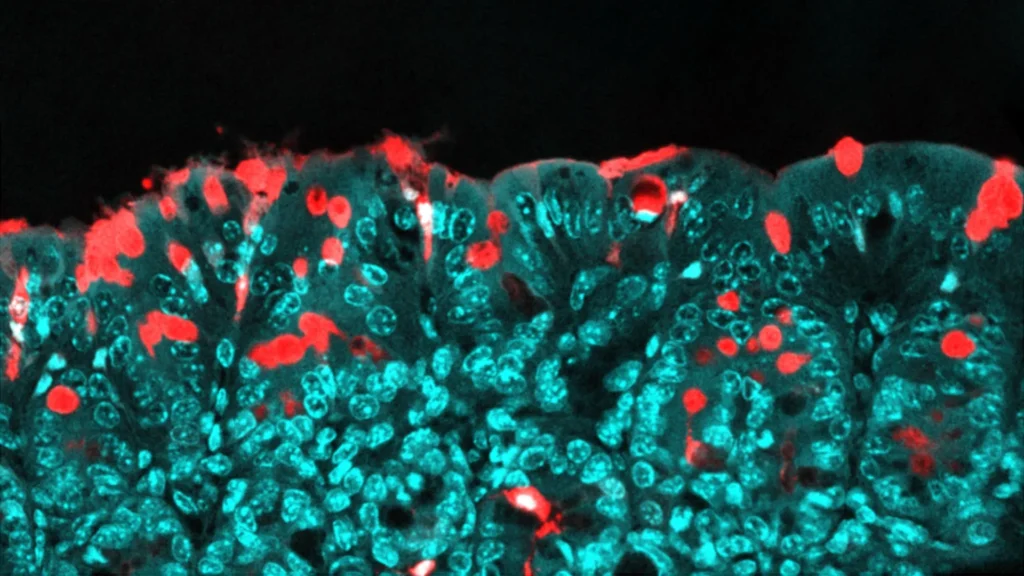

The altered microbiota included higher levels of flagellated bacteria, which are known to activate the immune system and promote inflammation. The researchers also observed that more bacteria were coming into close contact with the gut lining. This process, described as bacterial “encroachment,” caused certain gut pathways to close earlier than normal. These pathways usually allow small bacterial fragments to cross the gut lining so the immune system can recognize them and learn to tolerate the body’s own microbiota.

When these pathways closed too soon in the offspring of emulsifier-exposed mothers, communication between the gut microbiota and the immune system was disrupted. As the animals reached adulthood, this disruption led to an overactive immune response and chronic inflammation, significantly increasing the risk of inflammatory gut diseases and obesity. The study links early-life microbiota changes in mice, even without direct emulsifier consumption, to a higher likelihood of developing these chronic conditions later on.

Implications for Human Health

“It is crucial for us to develop a better understanding of how what we eat can influence future generations’ health. These findings highlight how important it is to regulate the use of food additives, especially in powdered baby formulas, which often contain such additives and are consumed at a critical moment for microbiota establishment. We want to continue this research with clinical trials to study mother-to-infant microbiota transmission, both in cases of maternal nutrition with or without food additives and in cases of infants directly exposed to these substances in baby formula,” comments Benoit Chassaing, last author of the study.

This work was funded by a Starting Grant and a Consolidator Grant from the European Research Council (ERC).